Muslim in 3D: Looking Beyond Faith at Culture, History, and Civilization

How my trip to Andalusia helped me see the layers of my identity

When I was in 9th grade, we studied Greek Mythology in English class. Our teacher, Ms. Hunt, regailed us with the stories of Medusa and Hercules, Narcissus and Midas. We needed this background, she said, to understand Shakespeare before we embarked on the journey of reading Twelfth Night. May, one of my best friends, sat right behind me in English class. We finished each other’s sentences and put our hands up constantly to ask questions. Ms. Hunt named us Castor and Pollux, the Gemini Twins, and told us to look it up. She spent the least amount of time on Zeus. Overrated.

When we’d finished with Greek Mythology, we spent the better part of a month studying the story of King Henry the Eighth. Again Ms. Hunt said this was important for context. We learned about Henry’s six marriages, about the English Reformation, about the allowance of divorce. We learned about Anne Boleyn’s courtship, and marriage, and beheading. We watched a movie in class called Anne of a Thousand Days, telling her story from start to finish.

King Henry, I concluded, was a despicable man, but by the time we were finished studying him, I also saw him a fascinating character, a celebrity to my 14 year-old inquiring mind. Learning that much about a historical figure automatically fueled my interest. It lay the groundwork for curiosity about the next English Royal that I would come across, from Elizabeth I to George III to Prince Harry and Megan Markle today.

One Ramadan when I was little, my dad read us nightly from a book called Men Around the Messenger. It told the stories of the Prophet Muhammad’s companions (peace be upon him - pbuh). We learned about Bilal, the enslaved companion who gained his freedom and became the first person to publicly make the call to prayer. We learned about Omar, the man who was on his way to kill Prophet Muhammad pbuh, when he found out his own sister had become Muslim, and ended up accepting Islam himself when he read verses from the Quran at her house.

These people, their life stories and sacrifices, were etched into my brain as inspirations. But I never saw them as historical figures, could never draw a line from their lives, over 1400 years ago, to the life I was living. Muslims study the Seerah, the life of Prophet Muhammad pbuh, diligently. We all know the big stories: the migration from Mecca to Medina, the Battle of Badr, the first revelation. But my knowledge of Islamic history dried up after the death of the Prophet. All the details disappeared, and I found myself zoomed out 30,000 feet, only to pick up the thread again around 1920, with the fall of the Ottoman empire, the last Caliphate, for — *waves hand* — reasons.

The space between the Prophet’s death and the fall of the empire was fuzzy to me. I had heard in passing about the golden age of an Islamic Civilization, leading the world in various disciplines. Science, poetry, medicine, philosophy, architecture, astronomy. Look into any modern innovation or convenience, and you could draw a line back to the Muslim thinker who had laid its groundwork: Coffee had first been used by Sufis to keep them awake for extra night worship. Modern surgery had grown from techniques for suturing and syringes invented by Medieval Muslim doctors. There were plenty of examples of the shining city on a hill in our history — Damascus, Medina, Grenada. But they stood there, devoid of context or history, disembodied from everything I knew.

As I was growing up, I would hear references to famous Muslim figures. Inventors like Ibn Sina and Ibn Firnas. The traveler Ibn Battuta. The names were forgettable to me, disappearing on the breeze as soon as they were spoken. I was told these people had had a great impact on Western thought, medicine and science, but I was skeptical. There they were when I went searching for them in encyclopedias, with their long list of accomplishments, but I couldn’t find them referenced in novels, in music, in art. Only Rumi, the great Persian Sufi poet, was well-known enough that he didn’t require explaining. Only Rumi could be counted on to have his words show up in Facebook posts, or be written on coffee mugs.

And so, my self was split in two. There was Noha, the aspiring writer. Noha, the watcher of Seinfeld and reader of CanLit. The attempted cosmopolitan young adult. The city cyclist. The hockey expert.

And there was Noha the Muslim, but she was reduced further. Noha the Muslim was reduced to a series of things she had to do — pray five times a day, fast during Ramadan, read Quran, wear hijab — and a series fo thing she couldn’t do — celebrate Christmas, drink alcohol, eat pepperoni pizza.

My mother, an educator, tried to expand this definition of Noha the Muslim. In the weekend Arabic school she had founded during my childhood, she would introduce plays and songs instead of having us work only out of a textbook. But the Arabic plays were stilted, their formal language so far removed from the Egyptian words I spoke at home, and the plots were sanitized, too low stakes to matter. Instead of appreciating the creativity she was introducing, I resented the extra time I had to spend away from my actual interests. I couldn’t just finish my three pages of homework and move on to the English novel I was reading. I had to finish my three pages and memorize dialogue.

This fall, I travelled with my husband and my brother-in-law to Andalusia in Southern Spain. We toured the gorgeous cathedrals that were built on the sites of old mosques. We saw the castles and fortresses that the Andalusian Muslims had built in the 7th to 13th centuries, stunning and ornate.

In Sevilla, we walked up the 35 ramps that would take us to the top of the church bell tower. It had once been a minaret, towering over the city a hundred meters into the sky from which the Mu’athin would call people to prayer. The cathedral doors still bore the original Arabic engravings, the word Allah written in calligraphy script, an invocation of God’s glory.

We went out for dinner that night and had tapas in a chaotic, buzzing restaurant. Servers bustled from table to table, putting down plates of aubergine with honey, oxtail, patatas bravas. I was giddy. Maybe it was from the whirlwind day we had had, from the fact that I had stood on what was essentially a glorified balcony and not panicked despite my fear of heights, from the lunch empanadas that had tasted so good I wanted more. Mostly though, I was giddy because a switch had flipped on inside me, and a realization was starting to dawn in my mind. My Muslimness, all these years, had been two-dimensional, had been held apart. While I had internalized and understood the basics, there was a depth I had been missing. And here it was, this depth of identity, this civilization, lifting itself off the page and fully forming, layered and profound.

Islam is, at its core, a religion, a commitment to One God and to His worship through the obedience of his messenger, Muhammad pbuh. And it really can be that simple. But it has begotten entire systems of being, entire cultures and civilizations, with all their glorious, real, living layers, with all the food and music and science and architecture and philosophy and poetry and life that that implies. This was what I had missed as a minority, as a person who squeezed my faith into the compartments where I could fit it.

And because those layers were real and not theoretical, it meant they could be messy. It meant that sometimes, the people in the stories, in the history, weren’t perfect. The Muslim historical figures in Andalusia had built several of those shining cities on a hill. They had been brilliant, had built a place that had been a hub for knowledge, for culture, for social exchange. They had also fought for control and power, against each other and against the Visigoths and the Normans. They had been petty at times, conniving at times, as humans are wont to be.

The next day in the car, on our way to Grenada, we spent some time listening to the audio book, The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain, by Maria Rosa Menocal, learning more about this place we were visiting as it had been a thousand years earlier. The history I had always found so daunting started to come into focus. So, the Ummayyads were beaten by the Abbasids in Damascus, but one survived, and he came to the farthest reaches of the Muslim empire, and he started his own Caliphate? And then that lasted in various forms for 7 centuries. And while that was happening in Andalusia, what was happening with the Abbasids? How did that empire change?

We looked it up. The Abbasid empire had ended with the sack of Baghdad by the Mongols, but by then various other Caliphates had sprouted up across the region, with the Abbasids line reappearing as the Mamluks in Egypt. And on and on we went, tracing the line of rulers and Kings and Pashas and Viziers until we had arrived at modern day Egypt. We had stitched together a single strand of Islamic civilizational history, in just one place, all the way from the Prophet’s death to the present day. I was once again Pollux, hungry to learn.

It was a small thing. And yet it meant so much.

The world in which I function pre-supposes a basic understanding of the British Monarchy, the American Revolution, North American history as told from a European Settler perspective. This knowledge is distilled and baked into the air. We absorb it by osmosis as we move through the universe, doing everything from watching tv to shopping. Conversely, when we look at the middle east, we know nothing about the history. We have no perspective. We’re just dropped into a chaotic, dysfunctional world and told, “this is how it is”. We act as though there is no explanation for how a whole massive region came to be the way it is, for how it fits into the jigsaw puzzle of the places we do give time and attention and worth.

I can see now that my mother, with the plays she had made me read, was trying to bring this culture off the page, to stretch it beyond a series of restraints and responsibilities, to show me the beauty and richness it held. I hadn’t been ready to see it at the time. I’m ready now.

Is there something layered and complex in your life that you’ve oversimplified? Are you looking at it differently now?

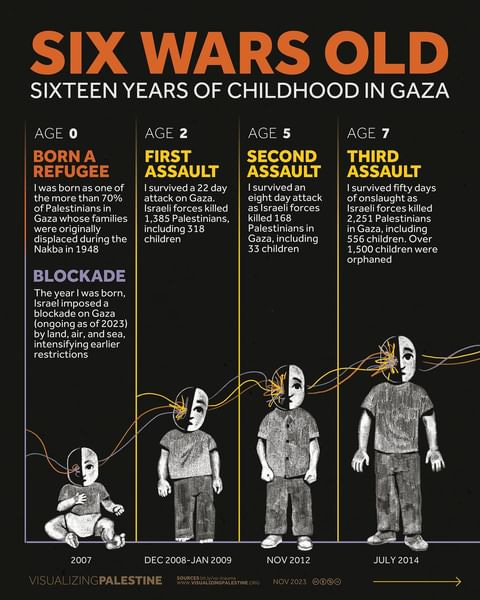

I am continuing to share resources, links, and information that I have found helpful regarding the crisis in Gaza and the West bank. The “humanitarian pause” has now ended, and conditions are worse than ever. Please continue to apply political pressure for a permanent ceasefire, an end to the blockade, and an end to the occupation. Please read and add your voice to those calling for equality for all.

If you haven’t yet spoken out, and you feel embarrassed to start now, it’s never too late. I’m here if you want to discuss this. There’s lots to work through, and maybe you have questions. It’s not too late to add your voice.

An interview with Gabor Mate, Holocaust survivor and the child of Holocaust survivors, world renowned trauma expert. Excellent resource for historical perspective and where to go from here. If you only follow through on one link I’ve posted, this is the one.

Local journalists on the ground, like Motaz Azaiza and Bisan, have reached their breaking point. I cannot imagine what they’re enduring, showing suffering, death and destruction, day and day out, begging for people to see the humanity of their people.

Cynthia Nixon, who is now on a hunger strike in protest of the massacres in Gaza.

American tax dollars are paying for these weapons, which are being used to kill indiscriminately. Tell your reps you don’t want this in your name.

Noha, this was absolutely beautiful. As you talked about the deep history of the Islamic world, I actually thought of Andalucía, before you mentioned it -- I spent a month there and a couple of days ago just hopped over to Morocco, and have been completely enthralled with the culture and beauty that have been preserved.

Though not the same, you also reminded me of my own childhood: I grew up in the Ethiopian Tewahedo Church, which is one of the oldest forms of Christianity in the world (3rd century AD) and it maintains a a very unique, rich cultural tradition; but because I grew up in the west, I always thought of Christianity as a “western” version -- Catholic, Protestant, etc. It was also a bit odd because most of Africa had been converted recently, while we had kind of isolated and kept to an old Christian tradition. I don’t practice religiously anymore, but I appreciate our Tewahedo cultura a lot more in its uniqueness and how it influenced our broader society.

Salaam! What a beautiful piece and powerful journey. Thank you for sharing, it's very inspirational and brought joy to my morning. I love how you bring it back to your mother in the end, and see how you weren't ready to see the wisdom and beauty then, but now you are. And I love this idea of a shift from a two-dimensional to a three-dimensional relationship, adding depth. Thank you!