If you enjoyed this post, hit that 🤍 button to help me reach more people. Thx!

How to Spot a Girl-Family

I grew up in a family of sisters, the third of four girls. Then my husband and I had two boys. The world looks different when you go from girl-sister to boy-mom.

Today I’m exploring life as a girl-sister through vignettes of my born family. In a later essay, I’ll write about life as a boy-mom.

1- The family that cries together, stays together

When I was pregnant with D, my sister Zeinab was pregnant with his cousin. In the summers, we all spent time at Mama and Baba’s house, piling onto the couches and beds. Someone always walking in or out of the backdoor, in or out of a bathroom, in or out of a conversation.

I had a weepy pregnancy. Come to think of it, I was consistently weepy until I turned 35. Now, at 41, I’ve dried up. Shriveled? There are no more tears. I rage sometimes. I roll my eyes with frustration, but the tears are rare and precious gifts that overlook me. As if to say, there! you wanted to be free of us and now you are. How do you like that?

That summer of the double pregnancy, I walked in one evening to find my other two sisters, Soraya and Aminah discussing open houses. Aminah lived in California. Soraya lived with me in Montreal. Why were they looking at houses? By this point, I’d been in Montreal two years, but my homesickness had not yet abated. I cornered Soraya. Promise me you’re not moving. You have to stay. Promise me. Promise.

And the weeping began.

Soraya was non-committal. Look, I don’t have plans to move, but I can’t promise anything either. She’s always been a vagabond. At 17, she finished high-school a semester early and absconded to Egypt, coming home with loud clothes and a louder voice, all brash comedy. Mid-way through the pandemic, she left me and went to London1. My adult life can be charted by a series of repeat incidents of Soraya, leaving.

Mama stopped tidying in the kitchen. Came and sat next to me. Held my heaving shoulders, started the ruqya2. But a dam had been breached. The tears were tidal. Sobs wracked my whole body. I couldn’t get over the possibility of Soraya moving back to Ottawa, but if I could block it from my mind, perhaps my tears and I might reach a détente.

The storm of emotion took thirty minutes to pass. By the end, I had the hiccups. Soraya and Aminah watched their every word, careful not to set me off again.

That’s when Zeinab came down from her nap. How were the open houses? she asked brightly and they all leapt to their feet, waving their arms - danger! danger!

Zeinab recoiled, not sure where the attack was coming from.

Noha’s just barely calmed down, Mama told her, recounting the whole ordeal.

To me, Zeinab’s response was the summation of what it means to grow up with sisters. I’ve been crying upstairs for the last 30 minutes. If I’d known, I would have come down so we could cry together.

2- Pregnant and hiding

My sisters and I traded off being pregnant the way you trade off a relay race. Nausea. Food aversions. The smell of flowers delivered to the door by one fiancé sending another to the bathroom to throw up. The sight of chicken. The smell of chicken. The taste of chicken.

Sometimes we didn’t trade off. Sometimes we broke the rules and decided to run the relay together.

Zeinab and I spent hours in Mama and Baba’s walk-in closet, nestled between the hanging clothes, shifting this way and that to make room for our bellies. We didn’t start out in the closet of course, but in the hallway, where the smell of chicken and onions cooking on the stovetop threatened to send us into bouts of gagging.

Step one would be to barricade ourselves in the first place we could find, which was my parents’ master bedroom. Step two would be to notice that the smell was still discernible to our oversensitive olfactory nerves. Step three would be to put another door between us for fortification. Step four would be to wait.

Zeinab’s kids would inevitably find us, needing this or that. Complaining of a brother or a cousin who had hit them, taken their toy, said something mean. Close the door! Close the door! We’d say, in a panic, needing to protect our gag reflexes before we could mediate and send them on their way.

The closet was stuffy, a cocoon of summer heat. The A/C hardly reached us. But we were back in each other’s confidence. The interruptions few and far between. And wasn’t that something like our childhood? Like the nights we’d spent, whispering late, taking turns falling in and out of sleep and waking?

3- Dolls and Pretend

We never bought new Barbies when we were little. Mama would scout garage sales for cast-offs, dolls no longer loved by another little girl within a 6 block radius. We would fight over the blonde ones, but only if their hair hadn’t been chopped off. Someone was always stuck with Christie or Becky.

We had lots of brand new paper-dolls, flimsy cutout cardboard drawings you could dress any way you wanted. For the office. For the park. I have a memory of sleeping over at Tante Lynne’s house, of her buying a new paper-doll for each of me and Soraya. Of eating candy and drinking hot chocolate.

For all the paper-dolls we accumulated, only one entered our collective consciousness: Wishnik.

Aminah, my oldest sister, had invented this name out of thin air. Long after Wishnik the doll was gone, Aminah played pretend as Wishnik the schoolgirl. In the game, she was a naughty student who had to be scolded by a stern teacher named Mrs. Soraya. Soraya was maybe 6 at the time, and there was nothing she loved more than scolding her oldest sister.

Wishnik! You didn’t write your name neatly enough! Wishnik, come back and clean up your desk! Wishnik, why didn’t you finish your homework? Mrs. Soraya’s arms would be folded across her chest, her eye-brow perpetually arched, her lips pursed.

Aminah was game then and she’s game now. She’s always been the sweetest, the smiley-est, the easiest to amuse. I keep saying when I grow up I want to be Aminah, but I’m grown now and I’m still much more snarky than she’s ever been.

4- Thirteen Tangents

Here is a story that has been told repeatedly to illustrate conversational dynamics in the Beshir household. One night over dinner, many moons ago, one of my sisters started to tell us all about something that had happened at school that day. Twenty-five minutes later, Baba quietly interrupted us all to say “thirteen”. We stopped to look at him. Thirteen what? Thirteen is an unlucky number, but we don’t believe in luck? Thirteen servings of bissilla3. Thirteen rides to school and back?

Thirteen tangents, Baba told us, since the sister in question had started to tell her story. And we still weren’t at the end. Poor Baba has always been the ragil ghalban4 in the midst of five female voices, the outnumbered, out-talked, out-storied man.

But Baba is a girl-dad, through and through. He may never have untangled the knots in our hair, but he taught each of us to ride our bikes, and then he took us for long rides along the river. Or he played soccer against us and our friends, one to 7, and dribbled the ball as though it was tied by a dainty little rope to his foot, a dance partner, refusing to leave him. Or he watched hockey with us, and tennis with us, and Columbo and Get Smart with us. Or he bought us secret ice creams at the mall before dinner, secret donuts at Tims on the way home, picking us up late from the bus stop when we had to stay at the library, working on group assignments.

Baba is my inverse identity, a man with a wife and daughters to my woman with a husband and sons. I look to his example when I’m struggling to read a complicated Lego manual, when the boys are yapping my ears off about an obscure Batman villain. I look to Baba’s shrugged shoulders, to his pretend resignation hiding secret delight. He loves every minute. I know this because I do too.

Thank you for reading Letters from a Muslim Woman. I share the joys and challenges of being a visibly Muslim woman in a sometimes-unfriendly world. A shoutout to our newest paid subscriber, Karima. Thanks so much for the support, Karima! A paid subscription is $5 a month and gives you access to my unfinished letters, published every other week, and my full archive. If you’re enjoying my perspective and want to support me, consider upgrading to help me spend more time on writing and share a voice that isn’t often heard.

If you can’t commit to a monthly subscription, but still want to support my work, you can buy me a coffee below. It helps me more than you realize.

I’m continuing to share resources about the situation in Gaza and the West Bank. This week, I’m sharing this post from Breaking the Silence Israel, a whistleblower group of former Israeli military officers, about the apathy of Palestinian civilian deaths deemed “collateral damage”. Please click through the carousel and read all the content, then ask why these lives are irrelevant while others matter.

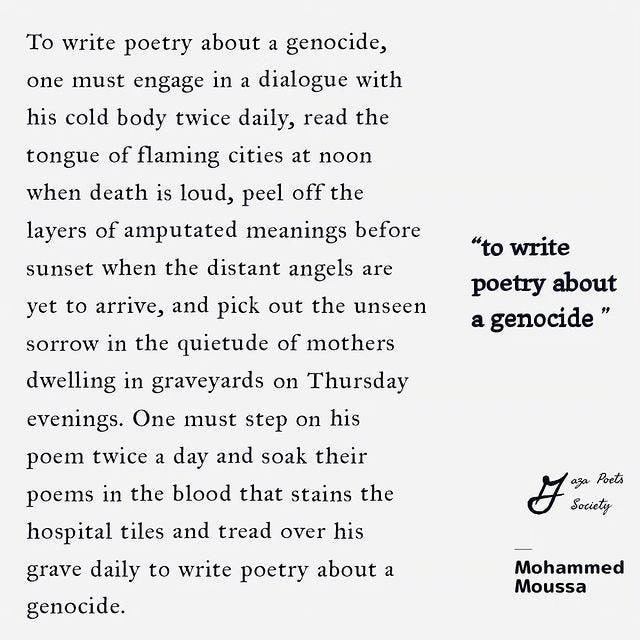

I also wanted to share this haunting poem that has stayed with me.

Let’s chat in the comments:

Do you have sisters or brothers? Was your family dominated by one or the other? How did it affect the vibe in your house?

Were you an emotional kid? Are you still emotional? Has your threshold changed as you grew?

Were you a mama’s boy or a daddy’s girl? How did that manifest for you?

To be clear, this is London, Ontario not London, England. Our response was always, really? That London?

“Ruqyah refers to the healing method based on the Quran and hadith through the recitation of the Quran, seeking of refuge, remembrance and supplication that is used as a means of treating sickness and other problems, by reading verses of the Quran, the names and attributes of Allah, or by using the prayers in Arabic or in a language the meaning of which is understood. The use of ruqyah as a method of treatment is popular among the Islamic alternative healing practitioners”. When we were little, my mother would read us the ruqyah by holding us and reading Quran or thikr over us to while she hugged us and let us cry. It always made me feel better. - reference: https://brill.com/view/journals/jqhs/14/2/article-p168_4.xml?language=en

Bissilla, sweet green peas, are cooked with ground beef or little beef cubes, diced onions, garlic, tomatoes and typical Egyptian spices (cumin, salt, pepper) in a traditional Egyptian dish.

Ragil Ghalban literally translates into “Poor man”. Not poor as in no money, poor as in, “the women in my life run the show and I’m just along for the ride.” This is a common joke in some Arab/Egyptian circles.

I am the oldest of four girls and the mother of 2 boys and 2 girls. My father’s favorite dinner time trick was to identify whose hair he had found.

I'm a father to three girls and the soccer sentence is poetic perfection.

"Or he played soccer against us and our friends, one to 7, and dribbled the ball as though it was tied by a dainty little rope to his foot, a dance partner, refusing to leave him."

Not sure my skills are up to Baba's, but I certainly relate. 😊