Welcome to Letters from a Muslim Woman!

I share the joys and challenges of being a visibly Muslim woman in a sometimes-unfriendly world.

If you’re new to this newsletter, here are a few good posts to give you the vibe of this space:

Before we get into today’s essay, I wanted to tell you about a very cool course being run by the Silk Road Institute, a wonderful not-for-profit in Canada dedicated to giving voice to Muslim and marginalized voices. Full disclosure, the Silk Road Institute is the brainchild of my husband and has been his passion project and volunteer, after-hours full-time job for the last 10 years.

Starting next week, they are hosting a virtual class with comedian Aliya Kanan to help aspiring comics develop their one-person show. You can find more info at this Instagram post and here with an awesome 40% discount code.

Now, on to this week’s essay!

Ramadan, the Muslim holy month of fasting, is around the corner. For this month, Muslims abstain from eating and drinking each day from dawn until sunset1. But the outer signs of Ramadan are only part of the story. It is also an opportunity to grow closer to God, to slow down our frenetic pace and spend more time in worship, praying taraweeh2 at night, dedicating time daily to read the Quran, feeding those less fortunate.

The Ramadans of my childhood are a whirlwind of memories. Evenings at the mosque, curled up on a jacket-come-blanket at my mother’s feet as taraweeh stretched on. Raucous iftars in the community centre gym. Folding tables stretched to fill the space, plastic table cloths covered with plates of dates. Foil trays of food as far as the hungry eye could see: tandoori chicken and rice, Egyptian pasta with bechamel sauce, Moroccan harissa soup, Lebanese fattoush salad.

At suhur, the pre-dawn meal we ate to get us through the day, my mom would make eggs and ful midammis3, that staple Egyptian legume, to fill us with protein and stave off our hunger. There was a stretch in high school when my mom decided we would get homemade french fries with every suhur. I thought little of it then, but in hindsight, I marvel at her energy, up at 3:30 a.m., cutting and deep-frying potatoes, then salting and wrapping them in a pita bread sandwich she’d carry up to our rooms.

There was a little song she’d sing to wake us up. I can still hear her voice, remember the words as she’d gently shake us awake and hold the sandwich inches from our mouths, the smell rousing us from sleep. Down we’d go, french fry sandwich in hand, to fill our bellies until that evening.

The memory of my childhood Ramadans made pandemic Ramadans almost unbearably isolating. When it was officially declared in March 2020, the pandemic meant the shuttering of mosques just ahead of their busy season. The holy month would start 5 weeks later. The communal night prayers, evening breakfasts, and pre-dawn suhurs were pre-emptively shut down.

When you’re a Muslim living in North America, Ramadan holds layers of importance. On a religious level, it’s the month in which the Holy Quran was first revealed to our Prophet Muhammad with the command to Read. On a social level, it’s one of the few opportunities to be all-encompassed in your Muslim identity. We shrink a lot, as minorities. We shrink to fit ourselves into molds that fit into the society around us, often without even realizing that we do it. But it’s hard to shrink when you’re abstaining from something so quotidian, so commonplace, as eating and drinking. It’s hard to shrink when your every moment is filled with fasting or praying or reading Quran.

In my house in the village of Chelsea, there were four of us: my husband and I, and our two boys, 9 and 6. How would I make the holy month special for them, these children who would miss not one, but two formative years of socializing and worshiping together? Left mosque-less, we converted our basement into our impromptu taraweeh and tahajjud4 space. Blue folding mattresses from Costco were dragged out of storage. Prayer mats were laid along the floor.

With no school to attend in the mornings that first year, the boys and I would spend the evening in our impromptu mosque after the final obligatory prayer of the night had been performed. Our taraweeh looked different than the formal ones led by imams. For one, we didn’t have enough Quran memorized to pray on our own, so we held our books in front of us to read directly from them. For another, we set our own schedule. Sometimes we performed the prayers in one shot and went to sleep. Other times we took turns waking and sleeping.

Again and again, I asked the boys if they’d rather go up to their beds. Every time the answer came back a resounding “no”. It was a worship-focused sleepover with Mama. There was a novelty to being together alone, past midnight, in our conversations with God. I can see them in my minds-eye, curled up on the mattresses, blankets pulled to their chins, prayer beads inches from their heads.

When the mosques re-opened over the various covid waves, first masked and distanced, and finally “back to normal” I gave a silent thanks in my heart.

There is something so precious about standing with hundreds of other worshippers, praying together, hearing the melodic recitation of an imam. There is something so precious about the crescendo of the Aameen, sung out by the entire congregation at the end of the fatiha.

But my sujood is not the same in congregation. I can’t take all the time in the world when I’m praying behind the imam, when his voice is dictating my motions. A part of me misses my private conversations with God, my private pleading and praising and lamenting. I can do it of course, by performing extra prayers on my own when I get home from the mosque. I can do it any time I want. But I’m busy and neglectful, and I tend to get home and get straight into bed to catch some sleep before the pre-dawn meal and the workday that will follow.

The mosques are open again this year, thank God. And so are the schools, and so are the malls and the theatres and the stadiums. The challenge will be to slow down, to actually lean into that connection instead of getting swept up in all the working and studying and watching and eating.

Pandemic Ramadans were tough but they took away the pretenses. Prophet Muhammad was in a cave, meditating alone, away from the city, when the Angel Gabriel first came to him with God’s commandment to read. Sometimes, we need to be alone to hear our own voices, and to hear the words God has sent to us as well.

A special shoutout to our newest paid subscribers,

and ! Thank you so much for your support, Stanley and Wake! A paid subscription is $7 a month. If you’re enjoying my perspective and want to support me, consider upgrading to help me spend more time on writing and share a voice that isn’t often heard.If you can’t commit to a monthly subscription, but still want to support my work, you can buy me a coffee below. It helps me more than you realize.

Let’s chat in the comments:

How did you find the pandemic in terms of holiday or special occasions, like birthdays?

Did you get any clarity on your inner voice by being alone during the pandemic? How about during another time?

Do you celebrate Ramadan? Do you lean into the social aspects of it?

I am continuing to share resources, links, and information that I have found helpful regarding the crisis in Gaza and the West bank. This week I’m sharing two pieces:

The first is an excellent explainer of the history of the West Bank by

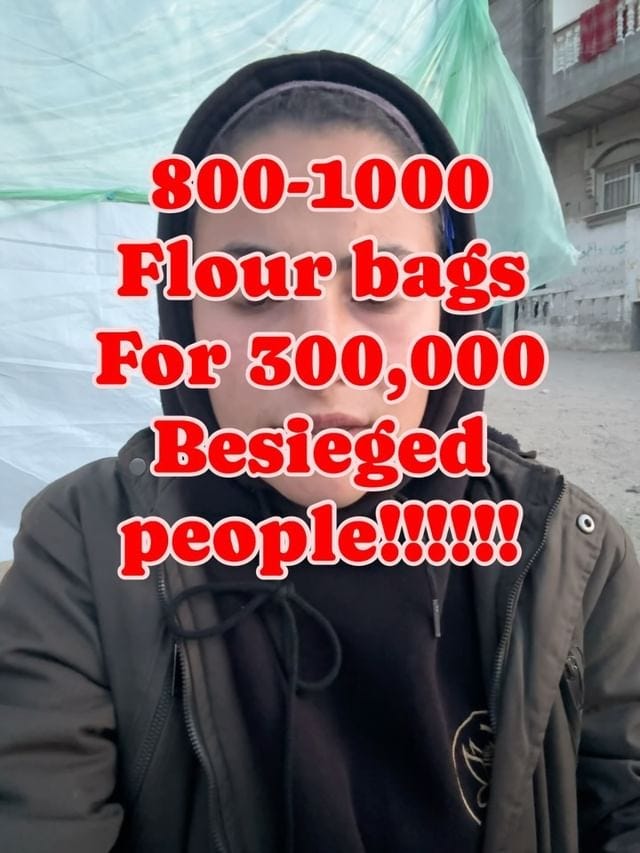

. This piece is a great way to inform yourself on the overall context.The second is this post by Gazan journalist Bisan Owda. All of Gaza is starving but Northern Gaza is particularly affected. People are desperate. They are eating grass and animal feed, and even that is running out. Join the movement to airdrop aid into Northern Gaza.

Fasting is compulsory for anyone who has reached puberty and can do so without medical issues. There are exemptions for the sick, the frail, and for travelers. Many children start to fast around the age of 8 or 9 and are pretty well old-hat by the time they actual reach puberty.

Taraweeh are extra voluntary prayers prayed only in Ramadan. They can be offered in community at the mosque, or also at home, in groups or alone. Taraweeh are prayed in sets of 2 rak’aas (units) of prayer, and can total anywhere from 8 to 11, to 21 rak’aas. The ones at the mosque often last about an hour. You can join the imam at any time and leave any time. In taraweeh at the mosque, the Imam usually starts Ramadan by reading from the beginning of the Quran and works his way through the whole book over the course of the month. There are 30 “sections” called Juz’ in the Quran, each about 20 pages long, so it lines up perfectly with the month long fasting affair.

Ful middammis is the delicious fava bean slow cooked and spiced with garlic, cumin, salt, pepper, olive oil, and often lime juice. It’s a go-to Egyptian breakfast or late supper food.

included a lovely Ode to Ful in her Egyptian magic series here.Tahajjud is yet another voluntary night prayer. What distinguishes it from Taraweeh is that it can be prayed any time of year, and is usually prayed alone, so it’s just a conversation between a worshipper and God. You can pray as many or as few rak’aas (units) in tahajjud as you want, but they are again, done in twos. Tahajjud is also distinguished by being prayed late in the night, often in the last third of the night, immediately before dawn. The challenge in pulling oneself from their cozy bed and blankets to wash and then stand before God alone, away from others’ judgement and praise, shows a personal and private dedication. I have been trying to build up to tahajjud and have mostly struggled. I think this is an indication of the need to purify my ego and my intention for His sake alone.

Just want to say, that in addition to reading Noha’s wonderful essays every week, the thoughtfulness that she puts into each response to a comment is just as beautiful to read 😊.

This essay has so much love and information for me, a non-Muslim. I’m thinking about how to best support my Muslim students during Ramadan. Maybe let them take that nap in class :)